FEATURED ARTICLE

Tax Planning for Realized Gains and Ordinary Income

Tax planning strategies for realized gains and ordinary income

Tax planning strategies for realized gains and ordinary income

Most trusts have a grantor, a trustee, and a beneficiary. Some trusts will have more than one of each. Sometimes, the grantor, the trustee, and the beneficiary are all the same person. In other cases, they’re different people.

There are actually two ways of defining the term “grantor.” The first is by looking at the trust agreement creating the trust. The trust agreement will identify the person who took the initiative of creating the trust as the “grantor.” So, for example, if you create a trust using Valur’s free software, you will be written into the trust agreement as the “grantor.” Because the grantor creates the trust, he or she has the right to name the trust’s beneficiaries and trustee.

The IRS has its own definition of the term “grantor,” though there is significant overlap between the two terms and, in fact, the two definitions rarely conflict. The IRS defines the term to mean the person who either creates the trust or funds it. Most trusts have a single grantor who both creates the trust and transfers assets to it. But sometimes, the IRS definition will result in there being two “grantors” of the trust even if only one person is described as the grantor in the trust agreement. For example, if you set up a trust, and fund it with $100, then later someone else funds the same trust with $50, the IRS will consider both of you to be the trust’s grantors.

The grantor is generally the person who creates the trust, so the grantor gets to determine what the trust says, what the trust is trying to accomplish, and who the beneficiaries and trustees are. Since trusts can last for generations (in some states, like South Dakota, trusts can last literally forever), the grantor’s decisions when he or she creates the trust may reverberate for many years to come.

The grantor can also matter for tax purposes. There are two types of trusts for income tax purposes: grantor trusts and non-grantor trusts. Grantor trusts are ignored for income tax purposes (but not necessarily for other purposes), which means that all of the income from a grantor trust is included on your income tax return. Non-grantor trusts are separate taxpayers and as a result file their own tax return and pay their own taxes. If a trust is a non-grantor trust, the identity of the grantor may not matter. But if the trust is a grantor trust, it matters a lot, because it determines who pays the income tax generated by the trust.

Grantors are sometimes referred to be other names. The two most common alternative names for grantor are “settlor,” “donor,” and “trustor.” But don’t be fooled! These words all mean the same thing.

Explore our tax planning tools to reduce taxable income and evaluate what trust is best for you, according to your situation. Or you can access more of our glossary definitions to know more!

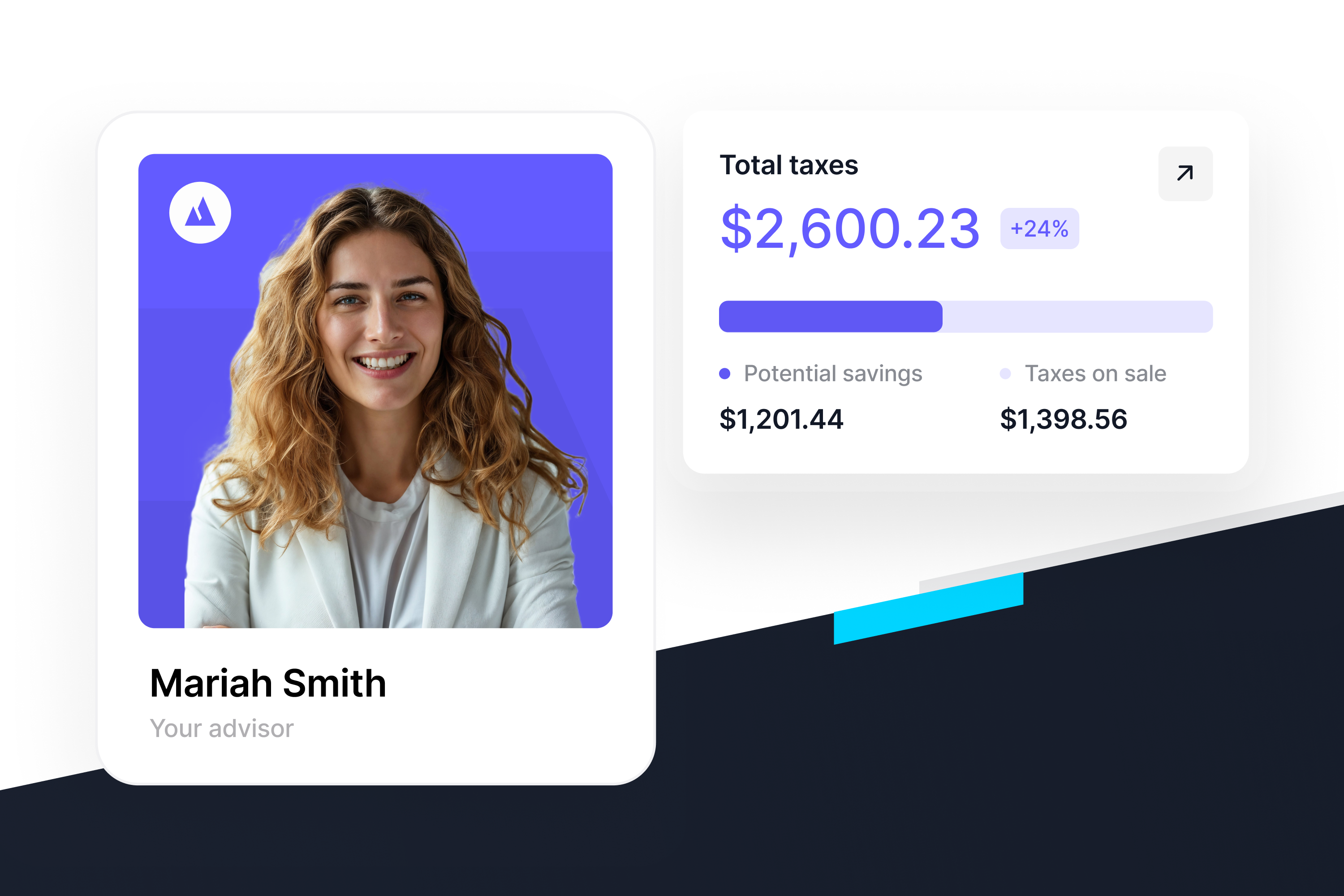

We’ve built a platform that makes advanced tax planning – once reserved for ultra-high-net-worth individuals – accessible to everyone. With Valur, you can reduce your taxes by six figures or more, at less than half the cost of traditional providers.

From selecting the right strategy to handling setup, administration, and ongoing optimization, we take care of the hard work so you don’t have to. The results speak for themselves: our customers have generated over $3 billion in additional wealth through our platform.

Want to see what Valur can do for you or your clients? Explore our Learning Center, use our online calculators to estimate your potential savings or schedule a time to chat with us today!