FEATURED ARTICLE

Tax Planning for Realized Gains and Ordinary Income

Tax planning strategies for realized gains and ordinary income

Tax planning strategies for realized gains and ordinary income

Most people have at least a basic understanding of how income taxes, property taxes, and sales taxes work. But, for high-net-worth Americans, there’s another set of taxes to worry about: wealth transfer taxes. These taxes are much less well understood. The most important wealth transfer tax is the federal estate tax, but there’s also a federal gift tax, a federal generation-skipping transfer tax, and state-level taxes. These taxes are significant, but they can be avoided to a great extent with proper planning. This article provides an overview of how these taxes work, how estate tax planning can mitigate them, and some common approaches to mitigating these taxes.

The estate tax is a tax on the assets that a person leaves to their heirs when they pass away. The estates of U.S. citizens and residents are taxed on all of their worldwide assets — including real estate, retirement accounts, brokerage accounts, crypto, intellectual property, and whatever else a person owns. The federal estate tax rate is a flat 40%, and any tax is due within nine months of a person’s death.

There are three important exceptions to the estate tax.

First, each individual has a basic exclusion amount, sometimes called a lifetime exemption. The exemption is large; it’s the reason most Americans never owe any estate tax. In 2026, the exemption is $15 million per person.

Second, amounts left to a person’s U.S. citizen spouse are not taxed. This prevents a surviving spouse from having to sell the family home or business to pay estate tax. However, when the surviving spouse dies, his or her estate (including the amount inherited from the deceased spouse) will be subject to estate tax.

Third, amounts left to charity are not taxed. Warren Buffett says he plans to leave the vast majority of his fortune to charity when he dies. That means that Buffett’s estate won’t be subject to much estate tax. Of course, most people want to leave the bulk of their estates to their family members.

It’s hard to overstate how important estate tax planning is for high-net-worth people. The federal estate tax is a serious obstacle to intergenerational wealth transfers. Under current law, the estate of a New Yorker who dies with $30 million in 2026 will owe around $10 million of state and federal estate tax. And yet, the estate of a billionaire New Yorker who dies in 2026 after doing careful estate tax planning may owe very little. That’s the power of estate tax planning.

The federal gift tax is a tax on gifts made during the transferor’s lifetime. It applies when the transferor is a U.S. citizen or resident. It also applies to non-resident aliens who transfer U.S. situs property, such as a house in Florida. Like the federal estate tax, it is levied at 40%, and it shares the same exemption amount with the estate tax (in 2026, $15 million). So, if you use $3 million of your gift tax exemption during your lifetime and you die in 2026, your remaining estate tax exemption will be $12 million.

The gift tax and the estate tax are functionally a single, unified tax: the gift tax applies to lifetime gifts and the estate tax applies to transfers upon death. But there’s a separate, second layer of federal tax, called the generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax, that applies to transfers to members of generations after your children’s generation (grandchildren, for example). The generation-skipping transfer tax also applies to transfers to non-family members who are 37.5 years or more younger than the donor. This tax is also levied at a rate of 40%, which means transfers to your grandchildren could be subject to an effective tax rate far in excess of 50%, even if you live in a low-tax state like Texas. Like the gift and estate tax exemption amount, the generation-skipping transfer tax exemption amount is $15 million in 2026.

Let’s assume you have used your full lifetime gift and GST exemption of $15 million and have $10 million that you want to gift to your heirs. If you directly gift that amount to your children, it will be subject to a 40% estate tax, leaving $6 million for your kids. If, instead, you gift that $10 million to your grandkids, it will be subject to a 40% estate tax and a 40% GST tax, leaving only $5 million for your grandkids! Fortunately, with proper estate planning that incorporates some of the solutions mentioned later in the article, you should be able to avoid most (or all) of those transfer taxes.

There are three types of state-level wealth transfer taxes. The most significant variety are the state-level estate taxes. Twelve states and the District of Columbia have state estate taxes. They apply to anyone who dies a resident of one of those states and is over the state’s exemption amount. They can also apply to non-residents who own property in one of those states. Most of these states have very low exemption amounts, much lower than the federal exemption amount. Oregon’s estate tax exemption amount is only $1,000,000. Unlike the federal estate tax, which is flat, state estate taxes tend to be progressive, beginning at rates as low as 0.80% and reaching as high as 20% in Hawaii and Washington State. Because the federal government provides a federal estate tax deduction for state estate taxes paid, effective combined federal/state estate tax rates top out at 52%.

Six states impose an inheritance tax. (Maryland is the only state that imposes both an estate tax and an inheritance tax.) Unlike an estate tax, which applies to the net value of the assets in a deceased person’s estate, an inheritance tax applies to the amount transferred to a given beneficiary. Inheritance tax rates can reach as high as 18%, but there are so many exclusions that in practice these taxes only apply in rare situations.

Finally, Connecticut imposes its own gift tax. Because Connecticut conforms to the federal gift tax exemption amount, this tax only applies to gifts that are already subject to federal gift tax. No other state currently imposes a gift tax.

Making lifetime gifts is almost always than not making lifetime gifts, assuming you are going to be above the estate tax exemption amount. There are a few reasons for that, but the most significant, and easiest to grasp, is that gifted assets are able to appreciate outside of the donor’s taxable estate. So, for example, if you have an asset that is currently worth $1 million but will be worth $10 million in a decade, you can either give it away now and use $1 million of gift tax exemption, give it away in a decade when doing so will use $10 million of exemption, or hold onto it until you die, at which point it could be worth tens of millions of dollars. From a gift and estate tax planning perspective, you want to use as little exemption as possible, and that means giving the asset away now.

There’s another major reason to make lifetime gifts sooner: to maximize the use of your exemption. By making gifts now, individuals can take full advantage of the current exemption amount. Locking in that exemption could save a donor’s heirs tens of millions of dollars.

Now you may be wondering what are the best ways to gift assets during your life (or before 2026). Below, we go into some of the strategies wealthy families use to pass assets on to future generations while minimizing transfer taxes!

There are lots of different estate tax planning strategies, but they almost all involve at least one irrevocable trust. That’s because irrevocable trusts are ideal vehicles for receiving gifted assets. Here are the four biggest advantages of gifting assets to irrevocable trusts rather than making outright gifts:

Valur generates and administers a wide variety of estate tax planning trusts, including:

Each year, an individual is allowed to gift up to a certain amount per donee without using his or her lifetime gift-tax exemption. There is no limit to the number of different gift recipients. In 2026, the dollar amount is $19,000 (because it’s adjusted for inflation, the dollar amount increases over time). So if you have three children and two parents, you can gift $19,000 to each of them each year, for a total of $114,000 per year. Your spouse has his or her own annual exclusions, so he or she can also gift $19,000 to each donee each year. If you make consistent annual exclusion gifts, over the course of a few decades you’ll be able to shift a large amount of wealth out of your estate, free of gift tax.

But what if you’d rather make annual exclusion gifts to a trust instead of outright gifts to individuals? You can do that, too, provided that the trust includes a special “Crummey” withdrawal provision. In order to claim the annual exclusion for a gift to a Crummey trust, the trustee has to send a letter to each adult beneficiary (or each minor beneficiary’s guardian) notifying him or her of the gifts (which Valur automates and takes care of for you).

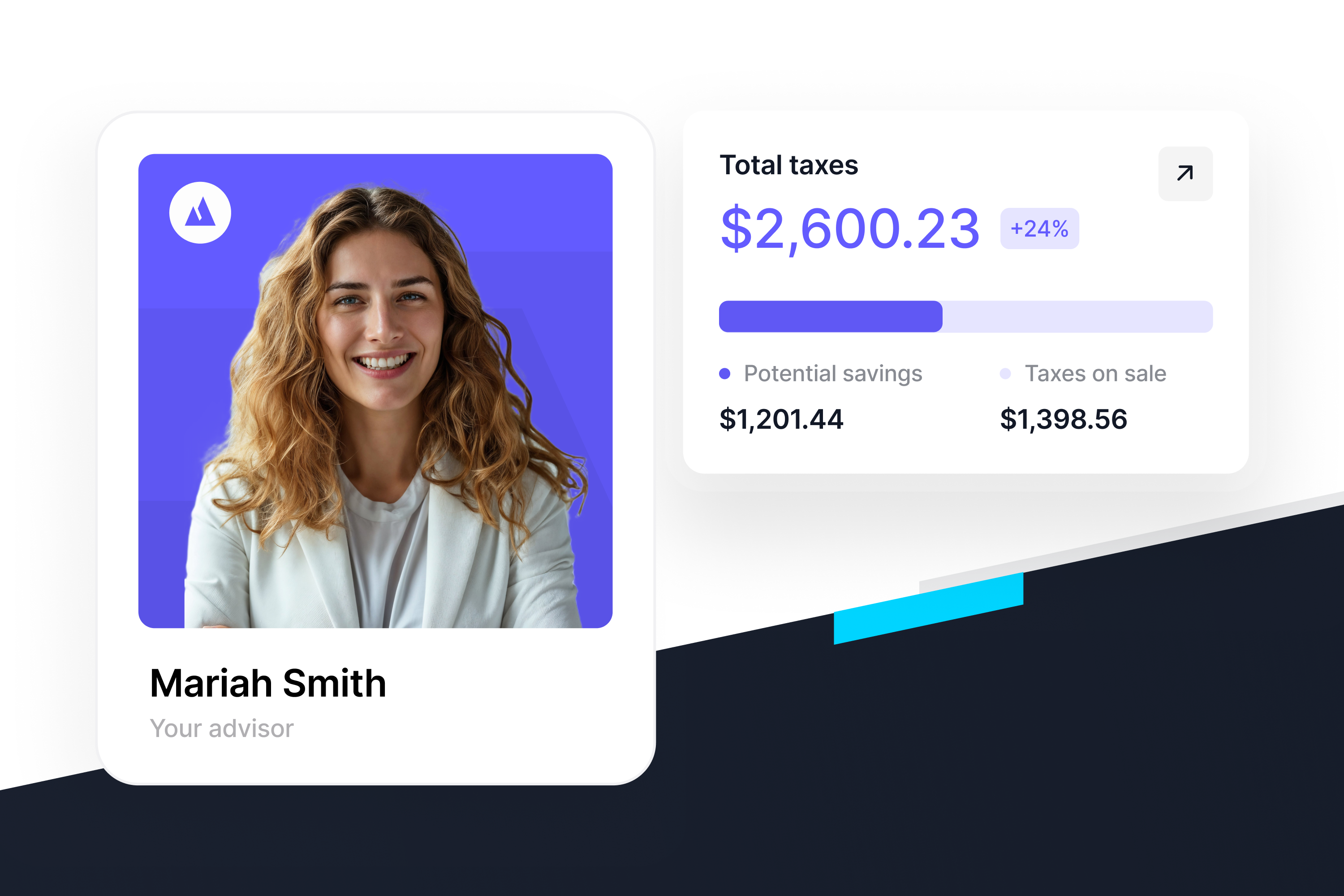

As your goals and financial situation change, so do your tax-planning needs. Our goal at Valur is to democratize knowledge about these solutions and to make the planning process seamless, so that everyone can take advantage of the best wealth-building solutions for them.

We’ve built a platform that makes advanced tax planning – once reserved for ultra-high-net-worth individuals – accessible to everyone. With Valur, you can reduce your taxes by six figures or more, at less than half the cost of traditional providers.

From selecting the right strategy to handling setup, administration, and ongoing optimization, we take care of the hard work so you don’t have to. The results speak for themselves: our customers have generated over $3 billion in additional wealth through our platform.

Want to see what Valur can do for you or your clients? Explore our Learning Center, use our online calculators to estimate your potential savings or schedule a time to chat with us today!